In 1843, Edward Dwyer was convicted at the Central Criminal Court, formerly the Old Bailey, of murdering his infant son, James Dwyer. He was sentenced to death.

The jury found that Edward had been severely provoked by the violent actions of his wife and recommended him to mercy. His wife, Bridget Dwyer, petitioned the Home Secretary asking him to recommend that the Crown mitigate the sentence under the Royal Prerogative of mercy. This was the only form of appeal against the verdict and the severity of a criminal sentence available at the time, and all such petitions were recorded in series HO 17 and HO 18 at The National Archives.

-

- From our collection

- HO 18/120/7

- Title

- Petitions from Bridget Dwyer recommending mercy for Edward Dwyer

- Date

- 1843

Bridget pleaded that the offence was committed in ‘a moment of excitement’ on the part of the prisoner when he dropped the child on a stone floor. The trial judge, Lord Denman, Lord Chief Justice, offered no view but the Home Secretary, without disclosing his reasons, recommended that the sentence was commuted to transportation for life. The petition is annotated: ‘Let the sentence of death be commuted to transportation for life and four years in Norfolk Island’.

Edward Dwyer

Under Sentence of Death in Horsemonger Lane Gaol for Murder.

Let his Sentence of Death be commuted to Transportation for Life and Four Years in Norfolk Island. JRG Graham

Lord Denman, in transmitting a Petition from the prisoner's Wife, states that he was recommended to Mercy by the Jury. Lord Denman offers no opinion upon the case.

Petition for Edward Dwyer. Catalogue reference: HO 18/120/7

The colony on Norfolk Island

Why did Sir James Graham, Home Secretary, nominate Norfolk Island as the place to which Dwyer should be transported?

Norfolk Island is situated about 1500km northeast of Sydney in the South Pacific Ocean. It is approximately eight km long and five km wide. In 1774, Cook sailed past Norfolk Island on his second voyage and claimed it for the Crown. Governor Arthur Phillips of New South Wales was concerned that the French might attempt to claim the island to gain a foothold in the Pacific, so he ordered Lieutenant Philip Gidley King of the Royal Navy to secure the island. He arrived with a crew of 22, soldiers and convicts, and after scrambling over the rocks they began the colonisation of the island.

Plan of Norfolk Island and view of the landing place in Cascade Bay, 1793. Catalogue reference: MPG 1/532 (2)

In the early 1820s, Norfolk Island was considered a suitable place for a penal colony primarily due to its remoteness and lack of a natural harbour. Initially, it was established to receive ‘colonial convicts’, namely convicts convicted for a second time and sentenced to transportation in a colonial court. Sir Ralph Darling, Governor of New South Wales in the 1820s, stated his objective in respect of Norfolk Island was to make it ‘a place of the extremest punishment, short of death’ for colonial convicts. Later, prisoners convicted in Britain, known as ‘probationary convicts’, were sent there.

Due to the harsh conditions and excessive punishments, a serious mutiny occurred on the island in January 1834. It involved more than 130 convicts who planned to take over the settlement, capture the next boat and sail to South America. The rebellion was quickly put down by the militia on the island, but left at least five convicts dead. The ringleaders were prosecuted, convicted and 13 men were executed.

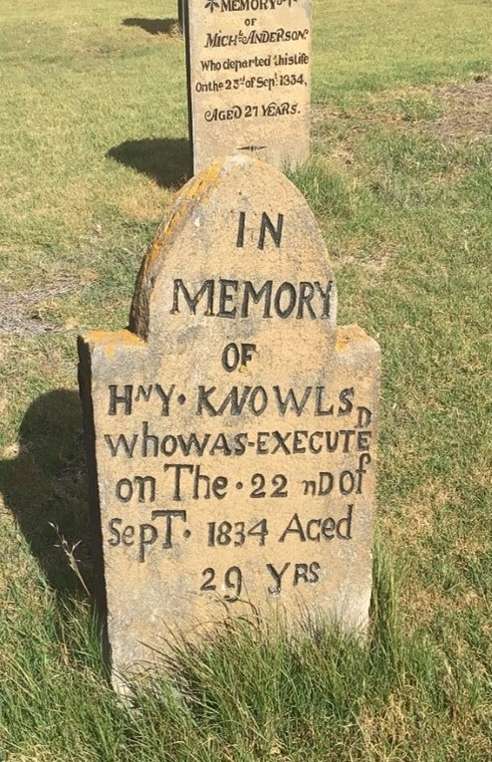

Interestingly, nine of their graves can still be seen in the island’s cemetery. This may be the only example of executed prisoners being buried in consecrated ground, as the usual practice was either to send the bodies for anatomisation or burial in unconsecrated ground.

In memory of Hny Knowls who was executed on the 22nd of Sept 1834 aged 29 yrs

Gravestone of Henry Knowles, prisoner and mutineer, executed 22 September 1834.

Following the publication of the Report from the Select Committee of the House of Commons on Transportation in 1838–9, known as the Molesworth Committee report, Norfolk Island was portrayed as a place of depravity and excessive punishment.

Sir Francis Forbes, a former Chief Justice of New South Wales, was asked by the committee what good was produced by inflicting so horrible a punishment as sending convicts to Norfolk Island. His reply was telling:

It did not produce any good. If it were to be put to himself, he should not hesitate to prefer death, under any form that it could be presented to him, rather than such a state of endurance as that of the convict on Norfolk Island.

Sir Francis Forbes, quoted in the Select Committee Report, 1838

Forbes was an advocate for the discontinuance of transportation. Moreover, there is no evidence that he ever visited Norfolk Island, but it was these types of remarks which reinforced the view that Norfolk Island was ‘a place of brutal extremes’ or ‘hell on earth.’ Not surprisingly, the report called for the abolition of transportation and the introduction of the penitentiary system.

Public disquiet forced Lord John Russell, Colonial Secretary, to act. By Order in Council of May 1840, no further convicts were to be sent to New South Wales, and the building of a new prison at Pentonville was initiated. He initially considered the abandonment of Norfolk Island as a penal colony, but this suggestion was resisted by the Governors of New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land. They argued that Norfolk Island was necessary to accommodate those convicts who repeatedly reoffended, and was the only effective deterrent.

However, Russell decided to trial a different system of management on Norfolk Island. He appointed Captain Maconochie, who had been a member of the Molesworth Committee, as Commandant. Maconochie advocated a ‘mark system’ which began in 1840. This system awarded ‘marks’ to prisoners for good conduct but ‘marks’ were lost for insolence, neglect of work etc.

At the time there were 1200 colonial convicts on the island and 699 ‘new hands’ were sent there. The system was bound to fail as the colonial authorities had no interest in it succeeding. Governor George Gipps of New South Wales was against it. He protested to the Colonial Secretary when he was ordered not to send any colonial convicts to Norfolk Island, as he considered it was the only suitable place for ‘incorrigible’ convicts.

A new system – and a riot

In 1841, after more than ten years in power, the Whigs were defeated. Lord Stanley was appointed Colonial Secretary in Sir Robert Peel’s government. He proposed a new system for the transportation of convicts. Only those sentenced to transportation for more than seven years would be sent abroad, and for the most serious offenders, like Edward Dwyer, this would be to Norfolk Island for four years.

Within months, Stanley had decided that Maconochie’s experiment was a failure and should end. He was recalled to London. Joseph Price was appointed the new Commandant. Although considered a strict disciplinarian, his administration was a failure.

In 1844–1845 reports were sent to London by Reverend Naylor and Robert Pringle Stuart, magistrate, stating that conditions on the island were so bad that anarchy was likely. They highlighted the prevalence of 'unnatural offences' and cited excessive punishments as the main cause of the unrest. They alleged that Lieutenant Governor Eardley Wilmot of Van Diemen’s Land had taken no active part in the supervision of Norfolk Island, and turned a blind eye to the punishments being inflicted there.

In July 1846, items of cutlery and cooking utensils belonging to the convicts were confiscated, and this led to ‘the Cooking Pot Riot’. Most of the items confiscated were painstakingly made by the convicts, often as love tokens. Taking away this last vestige of individualism and ordering that food was to be cooked and served collectively was the catalyst for revolt. Four officials were murdered and subsequently 12 convicts were convicted and hanged. Unlike the executed convicts in 1834, their bodies were put in an old sawpit outside the white picket fence surrounding the cemetery, now known as Murderers’ Mound.

Sacred to the Memory of Stephen Smith. 40. Native of Dublin.

Free overseer at Norfolk Island, who was barbarously murdered by a body of prisoners on the 1st of July, 1840, whilst in the execution of his duty at the Settlement Cook house, leaving a wife and three children to lament his loss.

Gravestone of Stephen Smith, overseer, victim of the Cooking Pot Riot, 1846.

Final years

Earl Grey had succeeded Stanley as Colonial Secretary in 1846. After news of the riot reached London, he took the decision that the penal settlement on Norfolk Island should be abandoned. All probationary convicts were sent to Van Diemen’s Land and more than 1200 prisoners were removed. About 460 colonial prisoners were left on the island.

Letter to S M Phillips warning of the proposed abandonment of Norfolk Island as a place of transportation. Catalogue reference: HO 45/1556

Succumbing to pressure from the colonial authorities, within months Grey had reversed this decision. It was left to Lieutenant Governor Denison of Van Diemen’s Land to decide the future of Norfolk Island.

He called for a report from the new Commandant, John Price. His deputy, C J Hampson, prepared a detailed assessment of how the penal settlement could continue to function. Hampson reviewed the circumstances leading up to the riot and made suggestions on how conditions could be improved. The three main suggestions were hope, hammocks and tobacco.

A new system of task work would be implemented to give hope to convicts. A few of the best-behaved colonial convicts would be sent on the next vessel to Van Diemen’s Land and so given hope that it was possible to leave the island. A ration of tobacco of one ounce per week would be issued to the convicts. All convicts would be accommodated in hammocks in an attempt to stop the ‘unnatural offences’ which had long caused consternation for the government.

Denison recommended the report to the Colonial Secretary and added his own observations. He argued that Norfolk Island was the only place of fear and deterrence for convicts who were sentenced to transportation in Van Diemen’s Land. He cited 25 examples of convicts, some of whom had been sentenced to transportation on four different occasions, and advised that the penal settlement on Norfolk Island should not be abandoned. Earl Grey accepted these recommendations.

In 1850, a detailed report on transportation in the colonies was prepared for submission to the Colonial Secretary and the Home Secretary. Norfolk Island was singled out for particular consideration.

-

- From our collection

- CO 885/2/12

- Title

- Memorandum on transportation by T. Frederick Elliot

- Date

- 24–25 January 1850

It reviewed government policy and concluded that the Norfolk Island penal colony should only be retained for those disobedient convicts who could not be restrained in any other colony. This recommendation was accepted and yet in the same year, probationary convicts were again sent to Norfolk Island. The Eliza sailed in 1850 with sixty convicts. A proportion of these were men who had been sentenced to seven years’ transportation – a clear case of the government adopting a policy but not following it.

-

- From our collection

- HO 11/16/105

- Title

- Register of convicts bound for Norfolk Island on the Eliza

- Date

- 12 December 1849

The penal establishment at Norfolk Island was abandoned in 1855 when all the convicts on the island were removed to Van Diemen’s Land, even though Van Diemen’s Land had ceased to be a penal colony two years earlier. The following year the descendants of the Bounty mutineers were allowed to settle there and many of their descendants still live there today.

A most unequal and uncertain punishment

In conclusion, why was Norfolk Island considered so much worse than other penal establishments?

Conditions on Bermuda were equally harsh, with reports of excessive punishments. There was a mutiny on Bermuda in 1830 and thousands of prisoners died of yellow fever there in the 1840s. For whatever reason, these episodes did not excite the same response or calls for its abandonment as occurred for Norfolk Island.

Likewise in Port Arthur in Van Diemen’s Land, convicts were subjected to a harsh system of punishment. Minor infringements of the rules were punished with prolonged periods in the gaol in silence and solitary confinement. The result of this was that the authorities had to build a lunatic asylum to accommodate the prisoners who suffered mental breakdowns from this treatment.

Yet it was Norfolk Island that successive governments considered as the place for the most disobedient convicts, and the ultra-penal colony. Perhaps it was the remoteness of the island and the damning reports of moral depravity which perpetuated this view. A view which successive governments were prepared to endorse as a deterrent to the most ‘incorrigible’ convicts.

There is no record of what Dwyer thought of the conditions on Norfolk Island, but the final observation should be left to the Report of the Molesworth Committee:

Transportation is a most unequal and uncertain punishment; [...] it is a mere lottery in which there are both many prizes and many blanks- the hope of obtaining prizes would with them, as with most gamblers, more than counterbalance the fear of blanks.

There was no doubt that successive governments made significant efforts to ensure that transportation to Norfolk Island was perceived as a ‘blank’ – there were no prizes for being sent there!

References

- Old Bailey Proceedings Online, November 1843. Trial of EDWARD DWYER (t18431127-267). Available at: http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/record/t18431127-267?text=Edward%20Dwyer (Accessed 22 February 2024)

- R Hughes, The Fatal Shore: A History of Transportation of Convicts to Australia (London, 1987)

- Valda Rigg, ‘Convict Life’ in Raymond Nobbs (ed), Norfolk Island and its Second Settlement, 1825-1855 (Sydney, 1991)

- T Causer, ‘Only a Place Fit for Angels and Eagles: The Norfolk Island Penal settlement, 1825-1855,’ Ph. D thesis, University of London, 2010

- ‘Report from the Select Committee of the House of Commons on Transportation, 1838’, House of Commons Papers, Vol 22, London, 1838

- U. R. Q. Henriques, “The Rise and Decline of the Separate System of Prison Discipline.” Past & Present, no. 54, 1972, pp. 61–93. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/650199 (Accessed 22 February 2024)

- Robert Pringle Stuart and Thomas Beagley Naylor, Norfolk Island, 1846: the accounts of Robert Pringle and Thomas Beagley Naylor (Adelaide, 1979)

- Report by CJ Hampson dated 10 March 1848, quoted in R. Montgomery Martin, The British Colonies, Extent, Condition and Resources, volume 5

- House of Commons Debate on The Convict System—Transportation, 8 March 1849, volume 103, cc. 383–424

- Brenda Mortimer, ‘Prisoners in Paradise,’ Ancestors (February 2009): pp 40–44

About the author

Dr Brenda Mortimer (LLB (Hons), Ph.D, Solicitor) is a long-serving volunteer at The National Archives, who has made an invaluable contribution to cataloguing petitions in Home Office series HO 17 and HO 18. She has lectured and written on the criminal justice system and transportation in the 19th century and her articles have been published in the UK and Australia.